Received

by Dillon Clark

Please click below to listen to an experimental audio version of the essay read by the author and mixed with field recordings

The summer opens with the hum of cicadas. In the background, everywhere I go in town, I hear their piercing, almost alarm-like sounds. As I go about my day, or step outside onto the porch I can hear them shaping the soundscape, from the trees above, registering, at times, above the hum of traffic or the whirring of tram sirens. For all their weight in marking the passage of time, I appreciate, simply, how strange they look. Up close, they’re quite ugly, almost otherworldly, and on the porch, while Michelle and I are outside talking, one of them whizzes by and scares her.

When approached, I notice that the cicadas stop producing sound. I try to get close to a bunch which nest in the mesquite tree in front of the apartment, but when I draw near and hold my recording device towards them, they go completely silent. A siren cut short. A small trace of the noise they make continues for just seconds, followed by nothing.

In a cafe, while I’m working, I hear a noise in the background, but when I try to listen in to it, I can’t tell if it’s the electricity of the refrigerators, the air-conditioning humming, or the cicadas dotting the trees outside, the sound they produce strong enough to pierce through layers of brick and glass.

*

On Mount Lemmon, birds are chirping, and people are gathering to hike, look at rock formations, peruse the gift shop in Summerhaven. I have a wind muff fitted over the end of my phone, taken from the package of the recording device I rented from the library, which died on my way up the mountain and couldn’t be charged by plugging into the cigarette lighter in the car. I came to collect sounds, and I figured that, at the very least, I should try to improvise. As I walk down the roads in Summerhaven to gather them, I get an awkward stare here or there. It’s strange, or jarring even I imagine, to watch someone walking around with a microphone recording things.

There’s the out-of-the-ordinariness of it, but I’m sure the main source of discomfort stems from the fact that the microphone is a recording device, and through recording, I’m not only making observations about things around me but also producing, at least in theory, a permanent record of what was observed. And it may be alarming, overwhelming even, to consider the fact that one’s voice can be placed into a permanent record somewhere. While I’m looking for mostly ambient sounds and trying to avoid direct recording of individuals, I can see how the situation can produce alarm as it raises questions in people making sound in a given place: am I being listened to? Why am I being listened to? For what purpose? What will you (the recorder), do with a recording of me? These fears, or questionings, center around power and consent. Consciously or subconsciously, the microphone as an object makes these questions and relations legible, perhaps this recognition is what translates outwardly as an awkward stare.

When I approach the cicadas, they stop humming whether I have a microphone or not. But I can’t help but wonder, ignoring their (re)action as only survival-based: are they thinking these questions, too? Do they not want me listening, observing them?

Is listening, an every-day act, wrought with dynamics of power, with immense ethical implications?

*

Sitting in the car, I listen to a voice-over recording of Greta Thunberg at the beginning of an album by English pop band The 1975, giving a speech about the climate crisis. In it, she talks about the failure of all our systems to tackle it, that the only solution that is possible now is sustained, continuous, and immediate civil disobedience. I begin to feel, in reflection, that collecting the sounds of living things is a morbid activity, and while I can’t pin-point each individual species that I’ve recorded in microphones, I can’t help feeling as if I’m amassing some kind of cemetery.

I’m reminded of the poet C.A. Conrad who—in one of their somatic exercises—mentioned they flooded their body with the sounds of extinct animals to write, hoping to summon what has died back into existence through making. As I hold the microphone to a hummingbird, trying to capture its wingbeats, I feel that, one day, whether I am alive for it or not, the sounds I’ve collected could become a lesser burial ground, like a vintage record on a dusty shelf, of what no longer exists. When I consider this, the most fearful parts of me wonder: how much time is left?

*

Another day of collecting sounds in Summerhaven. I pull off onto the shoulder of the road heading down-mountain to check in with the soundscape. I get out of the car, but hear dinging coming from behind me, having forgotten my keys in the ignition. This sound is new—something else I hadn’t found before—so I pull out my phone to record. At first, I don’t think much of it: what an interesting noise to add to the final composition, something else to layer in or provide texture. But it dawns on me later.

I’m recording an alarm.

*

Outside a cafe, I overhear someone near-yelling. They’re complaining about ethical non-monogamy ruining the institution of marriage. At first rectaction, I wonder: why are you so concerned about what somebody else is doing? But I consider it more, trying to parse the line of thought. This thinking destests another’s life, no matter the way in which that life is lived. The rhetorical formation of it is about control and conformity: about shoe-horning another into rigid hierarchical standards imposed by systems of power onto others who don’t fit into the categories of those in power. It rejects difference or understanding, earmarks conformity as virtue. It pushes individualism to an extreme where the individual feels as if they can force their self outwards to erase everything, everyone, who doesn’t fit that brand of living. This line of thinking doesn’t allow any multiplicity and deems difference as offensive. Bluntly, it equates to the I can be me, but you can’t be you strain of thought, and then, it is applied to anyone or anything that’s not American enough.

Another election year looms. And the rhetoric of this ideology is building all around, both online and in the street. It’s strange to be in this position again and again: As it emerged from where it’s been hiding eight years ago, I was starting college, and now, nearing the end of graduate school, it’s repeating, like an echo. What terrifies me most is this iteration’s shift: it has never not been violent, but its violence and loudness are increasing as it amplifies itself, as documents appear to detail its codification.

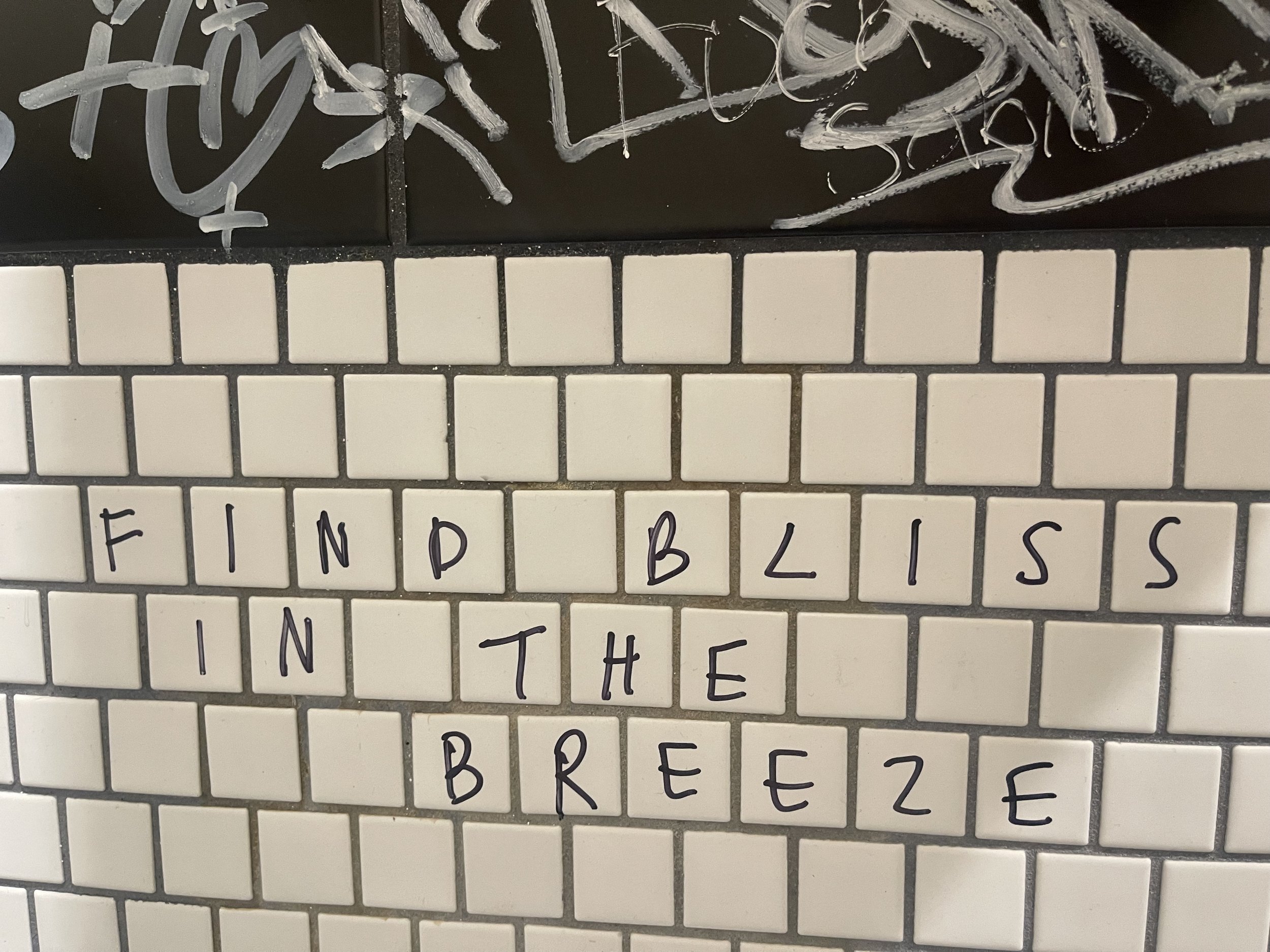

Maybe sound can teach us a way around, through, this ideology. There is a non-domination possible in noise.

I’m frustrated while trying to gather sounds, say of one particular bird, a particular cicada on a mesquite, or a specific plane droning overhead. No matter where or what, there’s always feedback in the background, a blending of the subject I’m trying to capture with wind, cars, trains, or my own feet walking. These layers make each recording not about one subject in particular—instead, offering a mess of noise piling together into a mass. Some sounds peek above others and then recede to allow other sounds room in the record. Nothing in what I’ve captured has to be about domination or control: the wind permits the cicadas, permits the whippoorwills, permits the street car bells to exist together.

It's this mass-ness that I want. Everything and nothing coiling around each other into one hulking thing. Birdsong and cars and people laughing and wind blowing.

*

But walking down the street, I hear a plane droning overhead. I only see one at first, but as the summer passes, more and more of them appear. I remember comments from friends, teachers telling me that when the planes travel in pairs the government is demo-ing the planes for sale. Every time they pass, then, I can hear arms sales, military exercises. Their noise pierces even the brick walls of my apartment, interrupting the afternoon.

The engines drown everything their roaring touches. The country always seems to prioritize war—it’s not surprising that, even locally, the soundscape reflects, and at times becomes dominated by, noises representing it. Right now, the sound of planes dominates. If we can deprioritize or resist militarization in our day-to-day lives, possibly our soundscape can come to reflect this shift in priorities. How? The prioritization of pleasure and the reallocating of resources seem possible avenues.

Enjoying things, and feeling joy from them, is generative: making time, when it feels like there is none, to wander a park with friends, listen to music, go to watch sunsets, little things that fill one's self up offer generativeness by replenishing—and by replenishing, they reject the goal of war: to destroy. These adjustments also reject capitalism. A sunset doesn’t benefit a bottom line. Joy at watching it produces only pleasure in one’s being. If the system/s which monetize the planes is interrupted, even at minute levels like altering our day-to-day activity, the oscillations of our in/actions, I hope, can be felt. Possibly, these oscillations can be heard, too, in a decrease in plane noise and an increase in natural noise. Maybe, even an increase in our own laughter.

This must be coupled with system changes as well: changing the allocations of money in the invisible web of the economy. I want less money for planes. I want this money directed to Michelle, my friend back home working at a library in Long Branch, to purchase books; I want this money directed to Kate, my friend working as a kindergarten guidance counselor, to purchase blueberry-scented markers for kids when they visit her to de-stress; I want this money directed to my friends who teach, so I can hear their joy when a student makes a powerful observation in class.

I want a future where no one makes their living by holding or shooting a gun, where guns aren’t worth anything, but people are.

When I finish writing for the day, I step out onto the porch. Another plane drones on overhead.

*

At one point, I had plans for what the work was supposed to do. I’d do this with the sounds, that with the writing. I’d blend the sounds in a specific way, layering them over each other in a predetermined order for an intended effect. But when it came time, the plans drifted: what came out was something that sounded boring and empty. Noise isn’t easy to contain, let alone intentionally shape—sounds are meant to bleed into and with each other to make a disjointed, even wonderfully ugly, whole. I realized at a point that I’d been trying to control things, make them neat and palatable, specific and useful. This way of making that I’d been engaging with the entire time was about control. And if there is anything that’s been revealed in striking upon it, it’s this: to command is a failed errand; domination creates deadness.

*

It’s a wild and joyful Tuesday: I pass the time by listening to SOPHIE and shaking my ass, roasting potatoes, and mixing up home-made honey mustard. Lisa, my neighbor downstairs, blasts Le Tigre so loud I can hear it through the floor, shouting one, two, three, four as the next instance of each chorus begins in the song. A light drizzle of rain patters on the window, a car alarm goes off outside, and the neighbor across the street, kitty-corner to me, is playing tag with his kids on the front lawn. The neighborhood is loud, it’s alive, and the sound of all our collective living brings me joy, knowing that we’re all here, making the best of things.

We’ve all collected and are contributing to shaping the sound of our shared space, but after we each quiet down, turn down the music, there’s no physical record of it, just a memory that I—or any of us—can recall and hold in ourselves, remember, misremember. It will become etched in us, written on us, recorded by our internal microphones.

*

Michelle and I go to look at the sunset at Gates Pass. She wakes me up from a nap and gets me out the door so I don’t have time to linger—it’s her last day visiting me in Tucson, and the sun is setting in forty minutes. We drive out to the west end of town, and I, stubborn, think I know how to get up to the overlook from memory. I get confused at a particular turn off from the road. My gut tells me to keep following, but my mind tells me otherwise. I listen to my mind, and end up getting us lost in the neighborhoods outside of Feliz Paseos Park. Swallowing my stubbornness, I turn on the GPS to get us back to the overlook.

We finally get to the top of the hill, just in time to see the tail end of the sunset from the parking lot. Slivers of the sun shine out from behind the mountains, the sky goes orange, and then pink, and finishes with threads of purple.

Michelle turns to me and says it’s quiet here. And I hadn't considered it before, but in this corner of the desert, it’s almost silent. There’s no planes to overtake the natural environment—only bugs buzzing or the wind picking up sand. And the silence isn’t suffocating, but freeing, able to permeate and be permeated by people, animals, wind. Like a membrane capturing the essence of living.

I am brought here: being present in place is the most important thing anyone, anything can do. When truly present, control recedes, and what is received is silence—not a silence of deadness, of the need to force into submission, of domination, but a silence out of the active acknowledgment that living is formless, membranic, a thing to imprint and be imprinted on, to be observed and observed by. When both conditions are true and understood, both the imprinting and being imprinted on, negotiation begins, each life opening dialogue with all the other lives around it.

As the dialogue begins, Michelle and I ready to leave. I have my car keys in my right hand and have at least attempted to offer myself up to this moment. There are no planes overhead—I am with a friend and listening to the sound of wind and bugs unimpeded, allowed to fill space.

I am here. I have been received.

References / Acknowledgements:

The information referenced draws on work discussed in graduate seminars taught by John Mellilo and Johanna Skibsrud, and is informed by dialogue with friends and teachers: thank you Farid, Wilson, Claude, Lynn, Nellie, Rocko, Michelle, and Matt.

The sound art piece presented with this essay is in dialogue with Nellie Papsdorf’s sound experiment and film, “THE FACILITY FOR REITERATION REPLAYS ME.”